In November 2021, Chris Friend interviewed the Pedagogy of the Digitally Oppressed Collective for the Teacher of the Ear episode on Care. Ashley Caranto Morford, Arun Jacob, and I were pleased to be on this show and think through the interview questions and conversation, an excerpt of which I’ve included below along with links to the full episode and transcript. Chris Friend is an Assistant Professor of English in New Media at Kean University and Associate Director of Hybrid Pedagogy.

Chris Friend: You shared some work on the Humanities Commons in which you all imagined Digital Humanities (DH) pedagogy as what you called “care work”. I’m just wondering if we could start this conversation with you saying what care work is in general and how—and this is where I’m stuck—how does teaching in DH do care work?

Ashley Caranto Morford: That’s a huge and hugely important question. As a practice of care and accountability, we acknowledge that we are connecting with one another from various sovereign indigenous lands. I myself am currently connecting to you all from Lenapehoking, the Lenape territory colonially called Philadelphia. As part of our care work, we recognize that many of the digital infrastructures we use are built on indigenous lands. So part of our care work practice is really being responsible and accountable to our obligations in these lands and in the digital spaces that extend from these lands. In terms of care work, more broadly, there is a quote from Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s work about making space accessible being an act of love for our communities, and when I think about the context of the digital, and making space accessible as being an act of love, I think that means access to digital technologies and infrastructure; access to spaces and communities and conversations through the use of digital technology, to think through care and collective access, as well as collective responsibility during an ongoing pandemic. And as educators, then this includes the ability to teach or for students to attend class asynchronously or with digital options and digital participation. I started off with this land acknowledgement because I think care work in digital space also means thinking about and being responsible to where and how digital infrastructures are being built on, through, and with the land. And so care work is always—even when we’re thinking about it in digital environments—is always extending out into the lands that we reside in, and are nourished by as well.

Kush Patel: I couldn’t help but think how care work within communities as well as a collective, within chosen kinships and even within professional settings, is what you do to survive on a day-to-day basis, to survive with each other—which is to say how not to think of care or care work as a commodity with exchange value, but rather as a relationship with life value. And which is to also then begin to spell out, name, and honor our dependencies on one another; dependencies with which we build strength in relation to each other, and continue to sort of work with those dependencies as we teach and learn in digital and online environments. Here, relationships, I’d stress, are not defined by one’s institutional settings, nor in the context of communities, are limiting of their possibilities to then have a much wider spectrum of engagement. And so we call this practice “deep care work”—that sense of emphasis on depth is to draw attention to both cultural as well as methodological dimensions of teaching and learning in the digital. bell hooks models for us what it means to work across differences of class and community, but in ways that does not distance us from kinships and communities that we may come from as well as those kinships and communities that we may be forming online and in digital environments.

Arun Jacob: So the way I would like to tackle your question of teaching DH and care work, and I think what comes to mind first and foremost for me, is the recognition of who we are. As DH practitioners, we are caretakers, and repair and maintenance workers, and this recognition of care, maintenance, and repair work is not only foundational to feminist politics and indigenous worldviews, but also fundamental to understanding how as teachers and learners there is an interdependence between the communities of the digital workspaces, our teaching and learning spaces between the people involved, and the environments from within which we emerge. So in that sense, it is the repair and maintenance work that resonates with me the most to think about the care-filled teaching and learning practice in DH.

(. . .) Listen to the full podcast episode; access the episode transcript; and read the complete listing of works consulted in this conversation on our Humanities Commons site (with cited authors included in the top image).

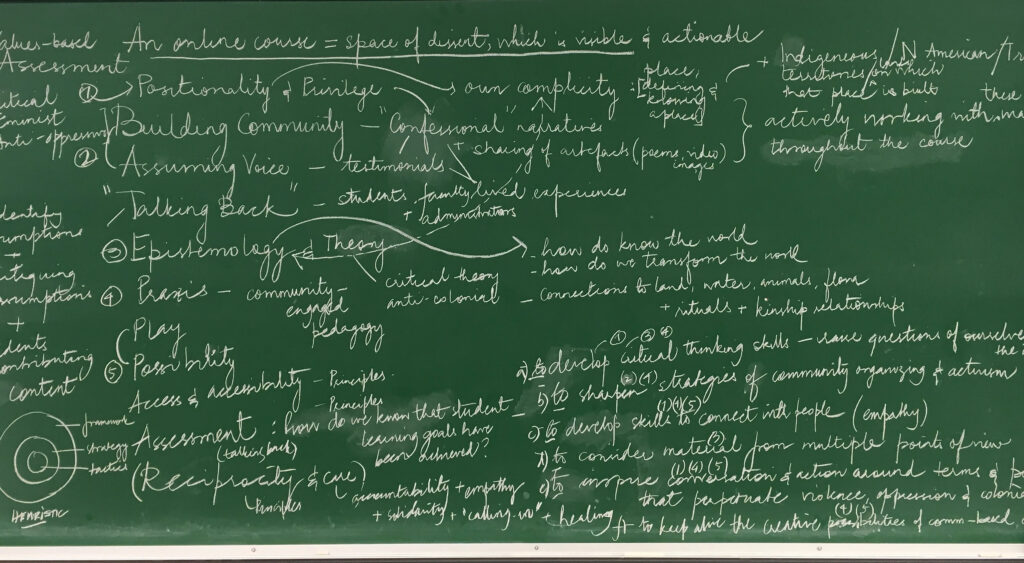

Image: Application Design, Teaching Toward Activism, #DHSI18 Critical Pedagogy and Digital Praxis in the Humanities Course (led by Chris Friend), University of Victoria, BC, June 2018.